I think this is a very interesting thread. Just giving out my two cents as somebody who is relatively new to the markets (2 years) on a few of the topics that were touched here.

On the idea of holding stocks for the long term:

I think one of the crucial insights you can gleam from successful investors is their understanding that there are cycles in which the economy transfers resources to its various constituent industries. There are companies within each industry that can turn out to be the most efficient and therefore the ones that get the better valuations, but there is no structural story as such.

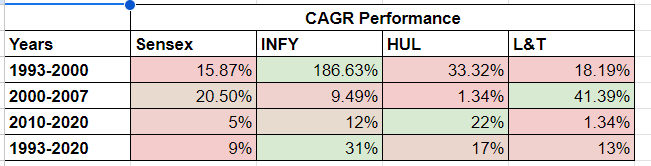

I’ll try to explain this idea by quoting Kenneth Andrade sir’s example of three industries that have been called structural sometime in their journey, or are still considered to be structural. These industries are FMCG, IT and Infrastructure. We’ll take the most capital efficient companies in these industries. And try to visualise the performance of these industries across three decades.

This chart demonstrates that while in the long run, you would have made money buying either of these three businesses because of their leadership and their capital efficient nature, you could have made much more had you been a little more cognizant of these cycles. This is the kind of outperformance retail investors are aiming to achieve on their small capital. And this is what we should aim to do.

Once we have the ambition set out, lets try to deduce what’s the pattern with this outperformance.

In this chart, if you see the outperformance of L&T in 2000 phase, it happened because of two things, one that the P/E of the company was at 8 times at the start of the cycle and two that the demand scenario for infrastructure increased tremendously over this period, taking it to 60 P/E by the end of the cycle.

HUL at the start of its benign cycle had a lower P/E than it does now, but more importantly, its period of outperformance was what economists have called the lost decade for Indian Growth. India didn’t grow as rapidly and so for businesses that were the largest in the country and were growing at higher than GDP, investors were willing to pay a higher P/E. This pushed the valuations of the company further.

So how can somebody predict these cycles? You can’t. And the only satisfactory answer I’ve gotten after hearing people like Kenneth Andrade is that you can’t predict the cycles but you can be more cognisant of patterns in the previous cycles, so you understand them well. But more importantly you can judge which are the companies that have the balance sheet and cash flow strength to capture the growth when it comes. The better question to ask is not which cycle is next, but which companies are generating a higher return on capital or are deploying lower capital, paying off their debt and managing to get higher cashflows whenever their parent sector is out of favour.

This will give you more time to really build conviction in a business and also wouldn’t be as time consuming as running after the latest stock on twitter while struggling in your professional commitments.

I think a good way of looking at it is in continuous cycles of what will do better one year down the road from here, instead of sitting on your laurels at any point.